Learning Objectives

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Associate physical quantities with their International System of Units (SI) and perform conversions among SI units using scientific notation

- Relate measurement uncertainty to significant figures and apply the rules for using significant figures in calculations

- Correctly create, label, and identify relationships in graphs using mathematical relationships (e.g., slope, y-intercept, inverse, quadratic and logarithmic)

| accuracy | ampere | constant |

| conversion factor | dependent variable | derived units |

| English units | exponential relationship | fundamental physical units |

| independent variable | inverse relationship | inversely proportional |

| kilogram | linear relationship | logarithmic (log) scale |

| log-log plot | meter | method of adding percents |

| order of magnitude | precision | quadratic relationship |

| scientific notation | second | semi-log plot |

| SI units | significant figures | slope |

| uncertainty | variable | y-intercept |

The Role of Units

The Role of Units

Physicists, like other scientists, make observations and ask basic questions. For example, how big is an object? How much mass does it have? How far did it travel? To answer these questions, they make measurements with various instruments (e.g., meter stick, balance, stopwatch, etc.).

The measurements of physical quantities are expressed in terms of units, which are standardized values. For example, the length of a race, which is a physical quantity, can be expressed in meters (for sprinters) or kilometers (for long distance runners). Without standardized units, it would be extremely difficult for scientists to express and compare measured values in a meaningful way (Figure 1.13).

All physical quantities in the International System of Units (SI) are expressed in terms of combinations of seven fundamental physical units, which are units for: length, mass, time, electric current, temperature, amount of a substance, and luminous intensity.

SI Units: Fundamental and Derived Units

SI Units: Fundamental and Derived Units

There are two major systems of units used in the world: SI units (acronym for the French Le Système International d’Unités, also known as the metric system), and English units (also known as the imperial system). English units were historically used in nations once ruled by the British Empire. Today, the United States is the only country that still uses English units extensively. Virtually every other country in the world now uses the metric system, which is the standard system agreed upon by scientists and mathematicians.

Some physical quantities are more fundamental than others. In physics, there are seven fundamental physical quantities that are measured in base or physical fundamental units: length, mass, time, electric current temperature, amount of substance, and luminous intensity. Units for other physical quantities (such as force, speed, and electric charge) described by mathematically combining these seven base units. In this course, we will mainly use five of these: length, mass, time, electric current and temperature. The units in which they are measured are the meter, kilogram, second, ampere, kelvin, mole, and candela (Table 1.1). All other units are made by mathematically combining the fundamental units. These are called derived units.

| Quantity | Name | Symbol |

|---|---|---|

| Length | Meter | m |

| Mass | Kilogram | kg |

| Time | Second | s |

| Electric current | Ampere | a |

| Temperature | Kelvin | k |

| Amount of substance | Mole | mol |

| Luminous intensity | Candela | cd |

The Meter

The SI unit for length is the meter (m). The definition of the meter has changed over time to become more accurate and precise. The meter was first defined in 1791 as 1/10,000,000 of the distance from the equator to the North Pole. This measurement was improved in 1889 by redefining the meter to be the distance between two engraved lines on a platinum-iridium bar. (The bar is now housed at the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, near Paris). By 1960, some distances could be measured more precisely by comparing them to wavelengths of light. The meter was redefined as 1,650,763.73 wavelengths of orange light emitted by krypton atoms. In 1983, the meter was given its present definition as the distance light travels in a vacuum in 1/ 299,792,458 of a second (Figure 1.14).

The Kilogram

The SI unit for mass is the kilogram (kg). It is defined to be the mass of a platinum-iridium cylinder, housed at the International Bureau of Weights and Measures near Paris. Exact replicas of the standard kilogram cylinder are kept in numerous locations throughout the world, such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, Maryland. The determination of all other masses can be done by comparing them with one of these standard kilograms.

The Second

The SI unit for time, the second (s) also has a long history. For many years it was defined as 1/86,400 of an average solar day. However, the average solar day is actually very gradually getting longer due to gradual slowing of Earth’s rotation. Accuracy in the fundamental units is essential, since all other measurements are derived from them. Therefore, a new standard was adopted to define the second in terms of a non-varying, or constant, physical phenomenon. One constant phenomenon is the very steady vibration of Cesium atoms, which can be observed and counted. This vibration forms the basis of the cesium atomic clock. In 1967, the second was redefined as the time required for 9,192,631,770 Cesium atom vibrations (Figure 1.15).

The Ampere

Electric current is measured in the ampere (A), named after Andre Ampere. You have probably heard of amperes, or amps, when people discuss electrical currents or electrical devices. Understanding an ampere requires a basic understanding of electricity and magnetism, something that will be explored in depth in later chapters of this book. Basically, two parallel wires with an electric current running through them will produce an attractive force on each other. One ampere is defined as the amount of electric current that will produce an attractive force of 2.7 10–7 newton per meter of separation between the two wires (the newton is the derived unit of force).

Kelvins

The SI unit of temperature is the kelvin (or kelvins, but not degrees kelvin). This scale is named after physicist William Thomson, Lord Kelvin, who was the first to call for an absolute temperature scale. The Kelvin scale is based on absolute zero. This is the point at which all thermal energy has been removed from all atoms or molecules in a system. This temperature, 0 K, is equal to −273.15 °C and −459.67 °F. Conveniently, the Kelvin scale actually changes in the same way as the Celsius scale. For example, the freezing point (0 °C) and boiling points of water (100 °C) are 100 degrees apart on the Celsius scale. These two temperatures are also 100 kelvins apart (freezing point = 273.15 K; boiling point = 373.15 K).

Metric Prefixes

Physical objects or phenomena may vary widely. For example, the size of objects varies from something very small (like an atom) to something very large (like a star). Yet the standard metric unit of length is the meter. So, the metric system includes many prefixes that can be attached to a unit. Each prefix is based on factors of 10 (10, 100, 1,000, etc., as well as 0.1, 0.01, 0.001, etc.). Table 1.2 gives the metric prefixes and symbols used to denote the different various factors of 10 in the metric system.

| Prefix | Symbol | Value | Example Name | Example Symbol | Example Value | Example Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| exa | E | 1018 | Exameter | Em | 1018 m | Distance light travels in a century |

| peta | P | 1015 | Petasecond | Ps | 1015 s | 30 million years |

| tera | T | 1012 | Terawatt | TW | 1012 W | Powerful laser output |

| giga | G | 109 | Gigahertz | GHz | 109 Hz | A microwave frequency |

| mega | M | 106 | Megacurie | MCi | 106 Ci | High radioactivity |

| kilo | k | 103 | Kilometer | km | 103 m | About 6/10 mile |

| hector | h | 102 | Hectoliter | hL | 102 L | 26 gallons |

| deka | da | 101 | Dekagram | dag | 101 g | Teaspoon of butter |

| ____ | ____ | 100 (=1) | ||||

| deci | d | 10–1 | Deciliter | dL | 10–1 L | Less than half a soda |

| centi | c | 10–2 | Centimeter | Cm | 10–2 m | Fingertip thickness |

| mili | m | 10–3 | Millimeter | Mm | 10–3 m | Flea at its shoulder |

| micro | µ | 10–6 | Micrometer | µm | 10–6 m | Detail in microscope |

| nano | n | 10–9 | Nanogram | Ng | 10–9 g | Small speck of dust |

| pico | p | 10–12 | Picofarad | pF | 10–12 F | Small capacitor in radio |

| femto | f | 10–15 | Femtometer | Fm | 10–15 m | Size of a proton |

| atto | a | 10–18 | Attosecond | as | 10–18 s | Time light takes to cross an atom |

See Appendix A for a discussion of powers of 10.

The metric system is convenient because conversions between metric units can be done simply by moving the decimal place of a number. This is because the metric prefixes are sequential powers of 10. There are 100 centimeters in a meter, 1000 meters in a kilometer, and so on. In nonmetric systems, such as U.S. customary units, the relationships are less simple—there are 12 inches in a foot, 5,280 feet in a mile, 4 quarts in a gallon, and so on. Another advantage of the metric system is that the same unit can be used over extremely large ranges of values simply by switching to the most-appropriate metric prefix. For example, distances in meters are suitable for building construction, but kilometers are used to describe road construction. Therefore, with the metric system, there is no need to invent new units when measuring very small or very large objects—you just have to move the decimal point (and use the appropriate prefix).

Known Ranges of Length, Mass, and Time

Table 1.3 lists known lengths, masses, and time measurements. You can see that scientists use a range of measurement units. This wide range demonstrates the vastness and complexity of the universe, as well as the breadth of phenomena physicists study. As you examine this table, note how the metric system allows us to discuss and compare an enormous range of phenomena, using one system of measurement (Figure 1.16 and Figure 1.17).

| Length (m) | Phenomenon Measured | Mass (kg) | Phenomenon Measured | Time (s) | Phenomenon Measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10–18 | Present experimental limit to smallest observable detail | 10–30 | Mass of an electron (9.11 10–31 kg) | 10–23 | Time for light to cross a proton |

| 10–15 | Diameter of a proton | 10–27 | Mass of a hydrogen atom (1.67 10–27 kg) | 10–22 | Mean life of an extremely unstable nucleus |

| 10–14 | Diameter of a uranium nucleus | 10–15 | Mass of a bacterium | 10–15 | Time for one oscillation of a visible light |

| 10–10 | Diameter of a hydrogen atom | 10–5 | Mass of a mosquito | 10–13 | Time for one vibration of an atom in a solid |

| 10–8 | Thickness of membranes in cell of living organism | 10–2 | Mass of a hummingbird | 10–8 | Time for one oscillation of an FM radio wave |

| 10–6 | Wavelength of visible light | 1 | Mass of a liter of water (about a quart) | 10–3 | Duration of a nerve impulse |

| 10–3 | Size of a grain of sand | 102 | Mass of a person | 1 | Time for one heartbeat |

| 1 | Height of a 4-year-old child | 103 | Mass of a car | 105 | One day (8.64 104 s) |

| 102 | Length of a football field | 108 | Mass of a large ship | 107 | One year (3.16 107 s) |

| 104 | Greatest ocean depth | 1012 | Mass of a large iceberg | 109 | About half the life expectancy of a human |

| 107 | Diameter of Earth | 1015 | Mass of the nucleus of a comet | 1011 | Recorded history |

| 1011 | Distance from Earth to the sun | 1023 | Mass of the moon (7.35 1022 kg) | 1017 | Age of Earth |

| 1016 | Distance traveled by light in 1 year (a light year) | 1025 | Mass of Earth (5.97 1024 kg) | 1018 | Age of the universe |

| 1021 | Diameter of the Milky Way Galaxy | 1030 | Mass of the sun (1.99 1024 kg) | ||

| 1022 | Distance from Earth to the nearest large galaxy (Andromeda) | 1042 | Mass of the Milky Way Galaxy (current upper limit) | ||

| 1026 | Distance from the Earth to the edges of the known universe | 1053 | Mass of the known universe (current upper limit) |

More precise values are in parentheses.

Using Scientific Notation with Physical Measurements

Using Scientific Notation with Physical Measurements

Scientific notation is a way of writing numbers that are too large or small to be conveniently written as a decimal. For example, consider the number 840,000,000,000,000. It’s a rather large number to write out. The scientific notation for this number is 8.40 1014. Scientific notation follows this general format

In this format x is the value of the measurement with all placeholder zeros removed. In the example above, x is 8.4. The x is multiplied by a factor, 10y, which indicates the number of placeholder zeros in the measurement. Placeholder zeros are those at the end of a number that is 10 or greater, and at the beginning of a decimal number that is less than 1. In the example above, the factor is 1014. This tells you that you should move the decimal point 14 positions to the right, filling in placeholder zeros as you go. In this case, moving the decimal point 14 places creates only 13 placeholder zeros, indicating that the actual measurement value is 840,000,000,000,000.

Numbers that are fractions can be indicated by scientific notation as well. Consider the number 0.0000045. Its scientific notation is 4.5 10–6. Its scientific notation has the same format

Here, x is 4.5. However, the value of y in the 10y factor is negative, which indicates that the measurement is a fraction of 1. Therefore, we move the decimal place to the left, for a negative y. In our example of 4.5 10–6, the decimal point would be moved to the left six times to yield the original number, which would be 0.0000045.

The term order of magnitude refers to the power of 10 when numbers are expressed in scientific notation. Quantities that have the same power of 10 when expressed in scientific notation, or come close to it, are said to be of the same order of magnitude. For example, the number 800 can be written as 8 102, and the number 450 can be written as 4.5 102. Both numbers have the same value for y. Therefore, 800 and 450 are of the same order of magnitude. Similarly, 101 and 99 would be regarded as the same order of magnitude, 102. Order of magnitude can be thought of as a ballpark estimate for the scale of a value. The diameter of an atom is on the order of 10−9 m, while the diameter of the sun is on the order of 109 m. These two values are 18 orders of magnitude apart.

Scientists make frequent use of scientific notation because of the vast range of physical measurements possible in the universe, such as the distance from Earth to the moon (Figure 1.18), or to the nearest star.

Unit Conversion and Dimensional Analysis

It is often necessary to convert from one type of unit to another. For example, if you are reading a European cookbook in the United States, some quantities may be expressed in liters and you need to convert them to cups. A Canadian tourist driving through the United States might want to convert miles to kilometers, to have a sense of how far away his next destination is. A doctor in the United States might convert a patient’s weight in pounds to kilograms.

Let’s consider a simple example of how to convert units within the metric system. How can we want to convert 1 hour to seconds?

Next, we need to determine a conversion factor relating meters to kilometers. A conversion factor is a ratio expressing how many of one unit are equal to another unit. A conversion factor is simply a fraction which equals 1. You can multiply any number by 1 and get the same value. When you multiply a number by a conversion factor, you are simply multiplying it by one. For example, the following are conversion factors: (1 foot)/(12 inches) = 1 to convert inches to feet, (1 meter)/(100 centimeters) = 1 to convert centimeters to meters, (1 minute)/(60 seconds) = 1 to convert seconds to minutes. In this case, we know that there are 1,000 meters in 1 kilometer.

Now we can set up our unit conversion. We will write the units that we have and then multiply them by the conversion factor (1 km/1,000m) = 1, so we are simply multiplying 80m by 1:

When there is a unit in the original number, and a unit in the denominator (bottom) of the conversion factor, the units cancel. In this case, hours and minutes cancel and the value in seconds remains.

You can use this method to convert between any types of unit, including between the U.S. customary system and metric system. Notice also that, although you can multiply and divide units algebraically, you cannot add or subtract different units. An expression like 10 km + 5 kg makes no sense. Even adding two lengths in different units, such as 10 km + 20 m does not make sense. You express both lengths in the same unit. See Appendix C for a more complete list of conversion factors.

Worked Example

Unit Conversions: A Short Drive Home

Suppose that you drive the 10.0 km from your university to home in 20.0 min. Calculate your average speed (a) in kilometers per hour (km/h) and (b) in meters per second (m/s). (Note—Average speed is distance traveled divided by time of travel.)

Strategy

First we calculate the average speed using the given units. Then we can get the average speed into the desired units by picking the correct conversion factor and multiplying by it. The correct conversion factor is the one that cancels the unwanted unit and leaves the desired unit in its place.

-

Calculate average speed. Average speed is distance traveled divided by time of travel. (Take this definition as a given for now—average speed and other motion concepts will be covered in a later module.) In equation form,

-

Substitute the given values for distance and time.

-

Convert km/min to km/h: multiply by the conversion factor that will cancel minutes and leave hours. That conversion factor is . Thus,

To check your answer, consider the following:

-

Be sure that you have properly cancelled the units in the unit conversion. If you have written the unit conversion factor upside down, the units will not cancel properly in the equation. If you accidentally get the ratio upside down, then the units will not cancel; rather, they will give you the wrong units as follows

which are obviously not the desired units of km/h.

- Check that the units of the final answer are the desired units. The problem asked us to solve for average speed in units of km/h and we have indeed obtained these units.

- Check the significant figures. Because each of the values given in the problem has three significant figures, the answer should also have three significant figures. The answer 30.0 km/h does indeed have three significant figures, so this is appropriate. Note that the significant figures in the conversion factor are not relevant because an hour is defined to be 60 min, so the precision of the conversion factor is perfect.

- Next, check whether the answer is reasonable. Let us consider some information from the problem—if you travel 10 km in a third of an hour (20 min), you would travel three times that far in an hour. The answer does seem reasonable.

There are several ways to convert the average speed into meters per second.

- Start with the answer to (a) and convert km/h to m/s. Two conversion factors are needed—one to convert hours to seconds, and another to convert kilometers to meters.

-

Multiplying by these yields

If we had started with 0.500 km/min, we would have needed different conversion factors, but the answer would have been the same: 8.33 m/s.

You may have noted that the answers in the worked example just covered were given to three digits. Why? When do you need to be concerned about the number of digits in something you calculate? Why not write down all the digits your calculator produces?

Worked Example

Using Physics to Evaluate Promotional Materials

A commemorative coin that is 2″ in diameter is advertised to be plated with 15 mg of gold. If the density of gold is 19.3 g/cc, and the amount of gold around the edge of the coin can be ignored, what is the thickness of the gold on the top and bottom faces of the coin?

Strategy

To solve this problem, the volume of the gold needs to be determined using the gold’s mass and density. Half of that volume is distributed on each face of the coin, and, for each face, the gold can be represented as a cylinder that is 2″ in diameter with a height equal to the thickness. Use the volume formula for a cylinder to determine the thickness.

The mass of the gold is given by the formula where and V is the volume. Solving for the volume gives

If t is the thickness, the volume corresponding to half the gold is where the 1″ radius has been converted to cm. Solving for the thickness gives

The amount of gold used is stated to be 15 mg, which is equivalent to a thickness of about 0.00019 mm. The mass figure may make the amount of gold sound larger, both because the number is much bigger (15 versus 0.00019), and because people may have a more intuitive feel for how much a millimeter is than for how much a milligram is. A simple analysis of this sort can clarify the significance of claims made by advertisers.

Accuracy, Precision and Significant Figures

Accuracy, Precision and Significant Figures

Science is based on experimentation that requires good measurements. The validity of a measurement can be described in terms of its accuracy and its precision (see Figure 1.19 and Figure 1.20). Accuracy is how close a measurement is to the correct value for that measurement. For example, let us say that you are measuring the length of standard piece of printer paper. The packaging in which you purchased the paper states that it is 11 inches long, and suppose this stated value is correct. You measure the length of the paper three times and obtain the following measurements: 11.1 inches, 11.2 inches, and 10.9 inches. These measurements are quite accurate because they are very close to the correct value of 11.0 inches. In contrast, if you had obtained a measurement of 12 inches, your measurement would not be very accurate. This is why measuring instruments are calibrated based on a known measurement. If the instrument consistently returns the correct value of the known measurement, it is safe for use in finding unknown values.

Precision states how well repeated measurements of something generate the same or similar results. Therefore, the precision of measurements refers to how close together the measurements are when you measure the same thing several times. One way to analyze the precision of measurements would be to determine the range, or difference between the lowest and the highest measured values. In the case of the printer paper measurements, the lowest value was 10.9 inches and the highest value was 11.2 inches. Thus, the measured values deviated from each other by, at most, 0.3 inches. These measurements were reasonably precise because they varied by only a fraction of an inch. However, if the measured values had been 10.9 inches, 11.1 inches, and 11.9 inches, then the measurements would not be very precise because there is a lot of variation from one measurement to another.

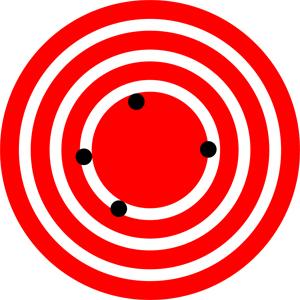

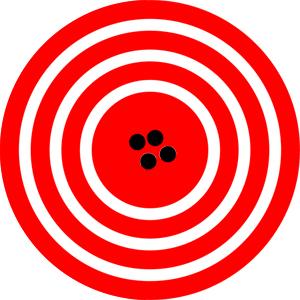

The measurements in the paper example are both accurate and precise, but in some cases, measurements are accurate but not precise, or they are precise but not accurate. Let us consider a GPS system that is attempting to locate the position of a restaurant in a city. Think of the restaurant location as existing at the center of a bull’s-eye target. Then think of each GPS attempt to locate the restaurant as a black dot on the bull’s eye.

In Figure 1.21, you can see that the GPS measurements are spread far apart from each other, but they are all relatively close to the actual location of the restaurant at the center of the target. This indicates a low precision, high accuracy measuring system. However, in Figure 1.22, the GPS measurements are concentrated quite closely to one another, but they are far away from the target location. This indicates a high precision, low accuracy measuring system. Finally, in Figure 1.23, the GPS is both precise and accurate, allowing the restaurant to be located.

Uncertainty

The accuracy and precision of a measuring system determine the uncertainty of its measurements. Uncertainty is a way to describe how much your measured value deviates from the actual value that the object has. If your measurements are not very accurate or precise, then the uncertainty of your values will be very high. In more general terms, uncertainty can be thought of as a disclaimer for your measured values. For example, if someone asked you to provide the mileage on your car, you might say that it is 45,000 miles, plus or minus 500 miles. The plus or minus amount is the uncertainty in your value. That is, you are indicating that the actual mileage of your car might be as low as 44,500 miles or as high as 45,500 miles, or anywhere in between. All measurements contain some amount of uncertainty. In our example of measuring the length of the paper, we might say that the length of the paper is 11 inches plus or minus 0.2 inches or 11.0 ± 0.2 inches. The uncertainty in a measurement, A, is often denoted as δA ("delta A"),

The factors contributing to uncertainty in a measurement include the following:

- Limitations of the measuring device

- The skill of the person making the measurement

- Irregularities in the object being measured

- Any other factors that affect the outcome (highly dependent on the situation)

In the printer paper example uncertainty could be caused by: the fact that the smallest division on the ruler is 0.1 inches, the person using the ruler has bad eyesight, or uncertainty caused by the paper cutting machine (e.g., one side of the paper is slightly longer than the other.) It is good practice to carefully consider all possible sources of uncertainty in a measurement and reduce or eliminate them,

Percent Uncertainty

One method of expressing uncertainty is as a percent of the measured value. If a measurement, A, is expressed with uncertainty, δA, the percent uncertainty is

Worked Example

Calculating Percent Uncertainty: A Bag of Apples

A grocery store sells 5-lb bags of apples. You purchase four bags over the course of a month and weigh the apples each time. You obtain the following measurements:

- Week 1 weight:

- Week 2 weight:

- Week 3 weight:

- Week 4 weight:

You determine that the weight of the 5 lb bag has an uncertainty of ±0.4 lb. What is the percent uncertainty of the bag’s weight?

Strategy

First, observe that the expected value of the bag’s weight, , is 5 lb. The uncertainty in this value, , is 0.4 lb. We can use the following equation to determine the percent uncertainty of the weight

Plug the known values into the equation

We can conclude that the weight of the apple bag is 5 lb ± 8 percent. Consider how this percent uncertainty would change if the bag of apples were half as heavy, but the uncertainty in the weight remained the same. Hint for future calculations: when calculating percent uncertainty, always remember that you must multiply the fraction by 100 percent. If you do not do this, you will have a decimal quantity, not a percent value.

Uncertainty in Calculations

There is an uncertainty in anything calculated from measured quantities. For example, the area of a floor calculated from measurements of its length and width has an uncertainty because the both the length and width have uncertainties. How big is the uncertainty in something you calculate by multiplication or division? If the measurements in the calculation have small uncertainties (a few percent or less), then the method of adding percents can be used. This method says that the percent uncertainty in a quantity calculated by multiplication or division is the sum of the percent uncertainties in the items used to make the calculation. For example, if a floor has a length of 4.00 m and a width of 3.00 m, with uncertainties of 2 percent and 1 percent, respectively, then the area of the floor is 12.0 m2 and has an uncertainty of 3 percent (expressed as an area this is 0.36 m2, which we round to 0.4 m2 since the area of the floor is given to a tenth of a square meter).

For a quick demonstration of the accuracy, precision, and uncertainty of measurements based upon the units of measurement, try this simulation. You will have the opportunity to measure the length and weight of a desk, using milli- versus centi- units. Which do you think will provide greater accuracy, precision and uncertainty when measuring the desk and the notepad in the simulation? Consider how the nature of the hypothesis or research question might influence how precise of a measuring tool you need to collect data.

Precision of Measuring Tools and Significant Figures

An important factor in the accuracy and precision of measurements is the precision of the measuring tool. In general, a precise measuring tool is one that can measure values in very small increments. For example, consider measuring the thickness of a coin. A standard ruler can measure thickness to the nearest millimeter, while a micrometer can measure the thickness to the nearest 0.005 millimeter. The micrometer is a more precise measuring tool because it can measure extremely small differences in thickness. The more precise the measuring tool, the more precise and accurate the measurements can be.

When we express measured values, we can only list as many digits as we initially measured with our measuring tool (such as the rulers shown in Figure 1.24). For example, if you use a standard ruler to measure the length of a stick, you may measure it with a decimeter ruler as 3.6 cm. You could not express this value as 3.65 cm because your measuring tool was not precise enough to measure a hundredth of a centimeter. It should be noted that the last digit in a measured value has been estimated in some way by the person performing the measurement. For example, the person measuring the length of a stick with a ruler notices that the stick length seems to be somewhere in between 36 mm and 37 mm. He or she must estimate the value of the last digit. The rule is that the last digit written down in a measurement is the first digit with some uncertainty. For example, the last measured value 36.5 mm has three digits, or three significant figures. The number of significant figures in a measurement indicates the precision of the measuring tool. The more precise a measuring tool is, the greater the number of significant figures it can report.

Zeros

Special consideration is given to zeros when counting significant figures. For example, the zeros in 0.053 are not significant because they are only placeholders that locate the decimal point. There are two significant figures in 0.053—the 5 and the 3. However, if the zero occurs between other significant figures, the zeros are significant. For example, both zeros in 10.053 are significant, as these zeros were actually measured. Therefore, the 10.053 placeholder has five significant figures. The zeros in 1300 may or may not be significant, depending on the style of writing numbers. They could mean the number is known to the last zero, or the zeros could be placeholders. So 1300 could have two, three, or four significant figures. To avoid this ambiguity, write 1300 in scientific notation as 1.3 × 103. Only significant figures are given in the x factor for a number in scientific notation (in the form ). Therefore, we know that 1 and 3 are the only significant digits in this number. In summary, zeros are significant except when they serve only as placeholders. Table 1.4 provides examples of the number of significant figures in various numbers.

| Number | Significant Figures | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1.657 | 4 | There are no zeros and all non-zero numbers are always significant. |

| 0.4578 | 4 | The first zero is only a placeholder for the decimal point. |

| 0.000458 | 3 | The first four zeros are placeholders needed to report the data to the ten-thousandths place. |

| 2000.56 | 6 | The three zeros are significant here because they occur between other significant figures. |

| 45,600 | 3 | With no underlines or scientific notation, we assume that the last two zeros are placeholders and are not significant. |

| 15895000 | 7 | The two underlined zeros are significant, while the last zero is not, as it is not underlined. |

| 5.457 1013 | 4 | In scientific notation, all numbers reported in front of the multiplication sign are significant |

| 6.520 10–23 | 4 | In scientific notation, all numbers reported in front of the multiplication sign are significant, including zeros. |

Significant Figures in Calculations

When combining measurements with different degrees of accuracy and precision, the number of significant digits in the final answer can be no greater than the number of significant digits in the least precise measured value. There are two different rules, one for multiplication and division and another rule for addition and subtraction, as discussed below.

-

For multiplication and division: The answer should have the same number of significant figures as the starting value with the fewest significant figures. For example, the area of a circle can be calculated from its radius using . Let us see how many significant figures the area will have if the radius has only two significant figures, for example, r = 2.0 m. Then, using a calculator that keeps eight significant figures, you would get

But because the radius has only two significant figures, the area calculated is meaningful only to two significant figures or

even though the value of is meaningful to at least eight digits.

-

For addition and subtraction: The answer should have the same number places (e.g. tens place, ones place, tenths place, etc.) as the least-precise starting value. Suppose that you buy 7.56 kg of potatoes in a grocery store as measured with a scale having a precision of 0.01 kg. Then you drop off 6.052 kg of potatoes at your laboratory as measured by a scale with a precision of 0.001 kg. Finally, you go home and add 13.7 kg of potatoes as measured by a bathroom scale with a precision of 0.1 kg. How many kilograms of potatoes do you now have, and how many significant figures are appropriate in the answer? The mass is found by simple addition and subtraction:

The least precise measurement is 13.7 kg. This measurement is expressed to the 0.1 decimal place, so our final answer must also be expressed to the 0.1 decimal place. Thus, the answer should be rounded to the tenths place, giving 15.2 kg. The same is true for non-decimal numbers. For example,

We cannot report the decimal places in the answer because 2 has no decimal places that would be significant. Therefore, we can only report to the ones place.

It is a good idea to keep extra significant figures while calculating, and to round off to the correct number of significant figures only in the final answers. The reason is that small errors from rounding while calculating can sometimes produce significant errors in the final answer. As an example, try calculating to obtain a final answer to only two significant figures. Keeping all significant during the calculation gives 48. Rounding to two significant figures in the middle of the calculation changes it to which is way off. You would similarly avoid rounding in the middle of the calculation in counting and in doing accounting, where many small numbers need to be added and subtracted accurately to give possibly much larger final numbers.

Significant Figures in this Text

In this textbook, most numbers are assumed to have three significant figures. Furthermore, consistent numbers of significant figures are used in all worked examples. You will note that an answer given to three digits is based on input good to at least three digits. If the input has fewer significant figures, the answer will also have fewer significant figures. Care is also taken that the number of significant figures is reasonable for the situation posed. In some topics, such as optics, more than three significant figures will be used. Finally, if a number is exact, such as the 2 in the formula, , it does not affect the number of significant figures in a calculation.

Worked Example

Approximating Vast Numbers: a Trillion Dollars

The U.S. federal deficit in the 2008 fiscal year was a little greater than $10 trillion. Most of us do not have any concept of how much even one trillion actually is. Suppose that you were given a trillion dollars in $100 bills. If you made 100-bill stacks, like that shown in Figure 1.25, and used them to evenly cover a football field (between the end zones), make an approximation of how high the money pile would become. (We will use feet/inches rather than meters here because football fields are measured in yards.) One of your friends says 3 in., while another says 10 ft. What do you think?

Strategy

When you imagine the situation, you probably envision thousands of small stacks of 100 wrapped $100 bills, such as you might see in movies or at a bank. Since this is an easy-to-approximate quantity, let us start there. We can find the volume of a stack of 100 bills, find out how many stacks make up one trillion dollars, and then set this volume equal to the area of the football field multiplied by the unknown height.

- Calculate the volume of a stack of 100 bills. The dimensions of a single bill are approximately 3 in. by 6 in. A stack of 100 of these is about 0.5 in. thick. So the total volume of a stack of 100 bills is

-

Calculate the number of stacks. Note that a trillion dollars is equal to , and a stack of one-hundred bills is equal to or . The number of stacks you will have is

1.3 -

Calculate the area of a football field in square inches. The area of a football field is , which gives . Because we are working in inches, we need to convert square yards to square inches

This conversion gives us for the area of the field. (Note that we are using only one significant figure in these calculations.)

- Calculate the total volume of the bills. The volume of all the $100-bill stacks is

- Calculate the height. To determine the height of the bills, use the following equation

The height of the money will be about 100 in. high. Converting this value to feet gives

The final approximate value is much higher than the early estimate of 3 in., but the other early estimate of 10 ft (120 in.) was roughly correct. How did the approximation measure up to your first guess? What can this exercise tell you in terms of rough guesstimates versus carefully calculated approximations?

In the example above, the final approximate value is much higher than the first friend’s early estimate of 3 in. However, the other friend’s early estimate of 10 ft. (120 in.) was roughly correct. How did the approximation measure up to your first guess? What can this exercise suggest about the value of rough guesstimates versus carefully calculated approximations?

Graphing in Physics

Graphing in Physics

Most results in science are presented in scientific journal articles using graphs. Graphs present data in a way that is easy to visualize for humans in general, especially someone unfamiliar with what is being studied. They are also useful for presenting large amounts of data or data with complicated trends in an easily-readable way.

One commonly-used graph in physics and other sciences is the line graph, probably because it is the best graph for showing how one quantity changes in response to the other. Let’s build a line graph based on the data in Table 1.5, which shows the measured distance that a train travels from its station versus time. Our two variables, or things that change along the graph, are time in minutes, and distance from the station, in kilometers. Remember that measured data may not have perfect accuracy.

| Time (min) | Distance from Station (km) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 24 |

| 20 | 36 |

| 30 | 60 |

| 40 | 84 |

| 50 | 97 |

| 60 | 116 |

| 70 | 140 |

- Draw the two axes. The horizontal axis, or x-axis, shows the independent variable, which is the variable that is controlled or manipulated. The vertical axis, or y-axis, shows the dependent variable, the non-manipulated variable that changes with (or is dependent on) the value of the independent variable. In the data above, time is the independent variable and should be plotted on the x-axis. Distance from the station is the dependent variable and should be plotted on the y-axis.

- Label each axes on the graph with the name of each variable, followed by the symbol for its units in parentheses. Be sure to leave room so that you can number each axis. In this example, use Time (min) as the label for the x-axis.

-

Next, you must determine the best scale to use for numbering each axis. Because the time values on the x-axis are taken every 10 minutes, we could easily number the x-axis from 0 to 70 minutes with a tick mark every 10 minutes. Likewise, the y-axis scale should start low enough and continue high enough to include all of the distance from station values. A scale from 0 km to 160 km should suffice, perhaps with a tick mark every 10 km.

In general, you want to pick a scale for both axes that 1) shows all of your data, and 2) makes it easy to identify trends in your data. If you make your scale too large, it will be harder to see how your data change. Likewise, the smaller and more fine you make your scale, the more space you will need to make the graph. The number of significant figures in the axis values should be coarser than the number of significant figures in the measurements.

- Now that your axes are ready, you can begin plotting your data. For the first data point, count along the x-axis until you find the 10 min tick mark. Then, count up from that point to the 10 km tick mark on the y-axis, and approximate where 22 km is along the y-axis. Place a dot at this location. Repeat for the other six data points (Figure 1.26).

Figure 1.26 The graph of the train’s distance from the station versus time from the exercise above.

- Add a title to the top of the graph to state what the graph is describing, such as the y-axis parameter vs. the x-axis parameter. In the graph shown here, the title is train motion. It could also be titled distance of the train from the station vs. time.

- Finally, with data points now on the graph, you should draw a trend line (Figure 1.27). The trend line represents the dependence you think the graph represents, so that the person who looks at your graph can see how close it is to the real data. In the present case, since the data points look like they ought to fall on a straight line, you would draw a straight line as the trend line. Draw it to come closest to all the points. Real data may have some inaccuracies, and the plotted points may not all fall on the trend line. In some cases, none of the data points fall exactly on the trend line.

Figure 1.27 The completed graph with the trend line included.

Analyzing a Graph Using Its Equation

One way to get a quick snapshot of a dataset is to look at the equation of its trend line. If the graph produces a straight line, the equation of the trend line takes the form

The b in the equation is the y-intercept while the m in the equation is the slope. The y-intercept tells you at what y value the line intersects the y-axis. In the case of the graph above, the y-intercept occurs at 0, at the very beginning of the graph. The y-intercept, therefore, lets you know immediately where on the y-axis the plot line begins.

The m in the equation is the slope. This value describes how much the line on the graph moves up or down on the y-axis along the line’s length. The slope is found using the following equation

In order to solve this equation, you need to pick two points on the line (preferably far apart on the line so the slope you calculate describes the line accurately). The quantities Y2 and Y1 represent the y-values from the two points on the line (not data points) that you picked, while X2 and X1 represent the two x-values of the those points.

What can the slope value tell you about the graph? The slope of a perfectly horizontal line will equal zero, while the slope of a perfectly vertical line will be undefined because you cannot divide by zero. A positive slope indicates that the line moves up the y-axis as the x-value increases while a negative slope means that the line moves down the y-axis. The more negative or positive the slope is, the steeper the line moves up or down, respectively. The slope of our graph in Figure 1.26 is calculated below based on the two endpoints of the line

Equation of line:

Because the x axis is time in minutes, we would actually be more likely to use the time t as the independent (x-axis) variable and write the equation as

The formula only applies to linear relationships, or ones that produce a straight line. Another common type of line in physics is the quadratic relationship, which occurs when one of the variables is squared. One quadratic relationship in physics is the relation between the speed of an object its centripetal acceleration, which is used to determine the force needed to keep an object moving in a circle. Another common relationship in physics is the inverse relationship, in which one variable decreases whenever the other variable increases. An example in physics is Coulomb’s law. As the distance between two charged objects increases, the electrical force between the two charged objects decreases. Inverse proportionality, such the relation between x and y in the equation

for some number k, is one particular kind of inverse relationship. A third commonly-seen relationship is the exponential relationship, in which a change in the independent variable produces a proportional change in the dependent variable. As the value of the dependent variable gets larger, its rate of growth also increases. For example, bacteria often reproduce at an exponential rate when grown under ideal conditions. As each generation passes, there are more and more bacteria to reproduce. As a result, the growth rate of the bacterial population increases every generation (Figure 1.28).

Using Logarithmic Scales in Graphing

Sometimes a variable can have a very large range of values. This presents a problem when you’re trying to figure out the best scale to use for your graph’s axes. One option is to use a logarithmic (log) scale. In a logarithmic scale, the value each mark labels is the previous mark’s value multiplied by some constant. For a log base 10 scale, each mark labels a value that is 10 times the value of the mark before it. Therefore, a base 10 logarithmic scale would be numbered: 0, 10, 100, 1,000, etc. You can see how the logarithmic scale covers a much larger range of values than the corresponding linear scale, in which the marks would label the values 0, 10, 20, 30, and so on.

If you use a logarithmic scale on one axis of the graph and a linear scale on the other axis, you are using a semi-log plot. The Richter scale, which measures the strength of earthquakes, uses a semi-log plot. The degree of ground movement is plotted on a logarithmic scale against the assigned intensity level of the earthquake, which ranges linearly from 1-10 (see Figure 1.29 (a)).

If a graph has both axes in a logarithmic scale, then it is referred to as a log-log plot. The relationship between the wavelength and frequency of electromagnetic radiation such as light is usually shown as a log-log plot (Figure 1.29 (b)). Log-log plots are also commonly used to describe exponential functions, such as radioactive decay.

Virtual Physics

Graphing Lines

In this simulation you will examine how changing the slope and y-intercept of an equation changes the appearance of a plotted line. Select slope-intercept form and drag the blue circles along the line to change the line’s characteristics. Then, play the line game and see if you can determine the slope or y-intercept of a given line.

How would the following changes affect a line that is neither horizontal nor vertical and has a positive slope?

- increase the slope but keeping the y-intercept constant

- increase the y-intercept but keeping the slope constant

- Increasing the slope will cause the line to rotate clockwise around the y-intercept. Increasing the y-intercept will cause the line to move vertically up on the graph without changing the line’s slope.

- Increasing the slope will cause the line to rotate counter-clockwise around the y-intercept. Increasing the y-intercept will cause the line to move vertically up on the graph without changing the line’s slope.

- Increasing the slope will cause the line to rotate clockwise around the y-intercept. Increasing the y-intercept will cause the line to move horizontally right on the graph without changing the line’s slope.

- Increasing the slope will cause the line to rotate counter-clockwise around the y-intercept. Increasing the y-intercept will cause the line to move horizontally right on the graph without changing the line’s slope.

Check Your Understanding

Check Your Understanding

- Conversion between units is easier in metric units.

- Comparison of physical quantities is easy in metric units.

- Metric units are more modern than English units.

- Metric units are based on powers of 2.

- 0.1 mi/h

- 27.8 mi/h

- 62 mi/h

- 160 mi/h

- Precision states how much repeated measurements generate the same or closely similar results, while accuracy states how close a measurement is to the true value of the measurement.

- Precision states how close a measurement is to the true value of the measurement, while accuracy states how much repeated measurements generate the same or closely similar result.

- Precision and accuracy are the same thing. They state how much repeated measurements generate the same or closely similar results.

- Precision and accuracy are the same thing. They state how close a measurement is to the true value of the measurement.