In modern short stories, characterization is just as important as plot—or even more important depending on the kind of story you are writing. Yet a short story author doesn’t always have the space to tell the readers everything about the characters through direct characterization. Most writers of short stories use indirect characterization, demonstrating their characters’ qualities through speech, thoughts, and actions.

Through indirect characterization, the author shows us what the character is like; in direct characterization, the author tells or describes the character’s traits. You may already know the difference between these “show and tell” approaches with characters, but take a look at a classic example of the direct characterization of a monarch in “The Lady, or the Tiger?” by Frank Stockton.

In the very olden time, there lived a semi-barbaric king, whose ideas, though somewhat polished and sharpened by the progressiveness of distant Latin neighbors, were still large, florid, and untrammeled, as became the half of him which was barbaric. He was a man of exuberant fancy, and, withal, of an authority so irresistible that, at his will, he turned his varied fancies into facts. He was greatly given to self-communing; and, when he and himself agreed upon anything, the thing was done.

Notice the adjectives Stockton uses to describe the king and his ideas, beginning with “semi-barbaric.” To ensure that you understand this important adjective, the author defines it in a context clue—“the half of him which was barbaric.”

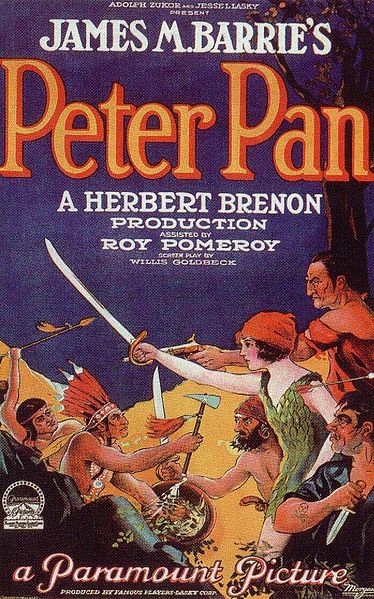

The next story provides an example of indirect characterization. It is an excerpt from James Barrie’s Peter and Wendy. We begin reading just as the Darlings are beginning a family. Look at the conversation that Mr. and Mrs. Darling have about the expense of caring for a child to see how Barrie characterizes Mr. Darling.

Wendy came first, then John, then Michael.

For a week or two after Wendy came it was doubtful whether they would be able to keep her, as she was another mouth to feed. Mr. Darling was frightfully proud of her, but he was very honourable, and he sat on the edge of Mrs. Darling’s bed, holding her hand and calculating expenses, while she looked at him imploringly. She wanted to risk it, come what might, but that was not his way; his way was with a pencil and a piece of paper, and if she confused him with suggestions he had to begin at the beginning again.

“Now don’t interrupt,” he would beg of her.

“I have one pound seventeen here, and two and six at the office; I can cut off my coffee at the office, say ten shillings, making two nine and six, with your eighteen and three makes three nine seven, with five naught naught in my cheque-book makes eight nine seven—who is that moving?—eight nine seven, dot and carry seven—don’t speak, my own—and the pound you lent to that man who came to the door—quiet, child—dot and carry child—there, you’ve done it!—did I say nine nine seven? Yes, I said nine nine seven; the question is, can we try it for a year on nine nine seven?”

“Of course we can, George,” she cried. But she was prejudiced in Wendy’s favour, and he was really the grander character of the two.

“Remember mumps,” he warned her almost threateningly, and off he went again. “Mumps one pound, that is what I have put down, but I daresay it will be more like thirty shillings—don’t speak—measles one five German measles half a guinea, makes two fifteen six—don’t waggle your finger—whooping-cough, say fifteen shillings”—and so on it went, and it added up differently each time; but at last Wendy just got through, with mumps reduced to twelve six, and the two kinds of measles treated as one.

As you read this excerpt, what do you learn about Mr. Darling’s character? How do you come to know these things about him? If you answered that he’s a man totally absorbed in accounting for the last cent, you would be correct. Barrie shows us this by first describing his actions, holding his wife’s hand while doing the absurd calculations that will determine whether they can keep the baby. Next, Barrie has Mr. Darling speak absurdly while he adds up figures and tries to fit Wendy into the budget. Barrie has him continue to add the cost of all the childhood illnesses that she might encounter. At the last moment, she comes in under the bottom line.

As Barrie characterizes Mr. Darling, readers get a feel for how this character speaks, thinks, and looks. They also see his actions and get a taste of how other characters react to him. Including as many of these methods as possible is an important step in creating a dynamic, round character who is ultimately believable.

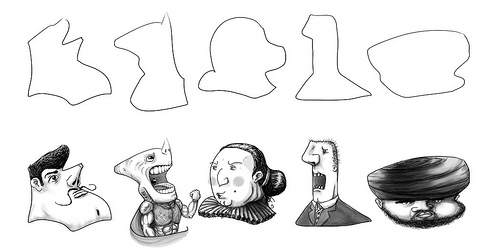

The STEAL mnemonic helps you remember ways you can show your imaginative characters to your readers:

| Speech |

What does the character say? How does the character speak? |

| Thoughts |

What is revealed through the character’s private thoughts and feelings? |

| Effect on others |

What is revealed through the character’s effect on other people?

How do other characters feel or behave in reaction to the character? |

| Actions |

What does the character do? How does the character behave? |

| Looks |

What does the character look like? How does the character dress? |

Using the STEAL chart above and Darling as your model, answer the questions posed. Write your responses using your notes. When you’re finished, check your understanding to see some possible responses.

Using the STEAL chart above and Darling as your model, answer the questions posed. Write your responses using your notes. When you’re finished, check your understanding to see some possible responses.

Think of two questions and write them using your notes. When you’re finished, check your understanding to see some possible responses.

Think of two questions and write them using your notes. When you’re finished, check your understanding to see some possible responses.