Higher Wages for Union Workers

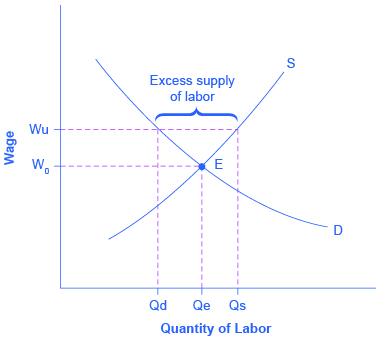

Why might union workers receive higher pay? What are the limits on how much higher pay they can receive? To analyze these questions, let’s consider a situation where all firms in an industry must negotiate with a single union, and no firm is allowed to hire nonunion labor. If no labor union existed in this market, then equilibrium (E) in the labor market would occur at the intersection of the demand for labor (D) and the supply of labor (S) in Figure 15.3. The union can, however, threaten that unless firms agree to the wages they demand, the workers will strike. As a result, the labor union manages to achieve, through negotiations with the firms, a union wage (Wu) for its members, above what the equilibrium wage would otherwise have been.

This labor market situation resembles what a monopoly firm does in selling a product, but in this case a union is a monopoly selling labor to firms. At the higher union wage Wu, the firms in this industry will hire less labor than they would have hired in equilibrium. Moreover, an excess supply of workers want union jobs, but firms will not be hiring for such jobs.

From the union point of view, workers who receive higher wages are better off. However, notice that the quantity of workers (Qd) hired at the union wage (Wu) is smaller than the quantity (Qe) that would have been hired at the original equilibrium wage. A sensible union must recognize that when it pushes up the wage, it also reduces the incentive of firms to hire. This situation does not necessarily mean that union workers are fired. Instead, it may be that when union workers move on to other jobs or retire, they are not always replaced. Or, perhaps when a firm expands production, it expands employment somewhat less with a higher union wage than it would have done with the lower equilibrium wage. Or, perhaps a firm decides to purchase inputs from nonunion producers, rather than producing them with its own highly paid unionized workers. Or, perhaps the firm moves or opens a new facility in a state or country where unions are less powerful.

From the firm’s point of view, the key question is whether the higher wage of union workers is matched by higher productivity. If so, then the firm can afford to pay the higher union wages and, indeed, the demand curve for unionized labor could actually shift to the right. This could reduce the job losses as the equilibrium employment level shifts to the right and the difference between the equilibrium and the union wages will have been reduced. If worker unionization does not increase productivity, then the higher union wage will cause lower profits, or losses, for the firm.

Union workers might have higher productivity than nonunion workers for a number of reasons. First, higher wages may elicit higher productivity. Second, union workers tend to stay longer at a given job, a trend that reduces the employer’s costs for training and hiring, and results in workers with more years of experience. Many unions also offer job training and apprenticeship programs.

In addition, firms that are confronted with union demands for higher wages may choose production methods that involve more physical capital and less labor, resulting in increased labor productivity. Table 15.3 provides an example. Assume that a firm can produce a home exercise cycle with three different combinations of labor and manufacturing equipment. Say that labor is paid $16 an hour, including benefits, and the machines for manufacturing cost $200 each. Under these circumstances, the total cost of producing a home exercise cycle will be lowest if the firm adopts the plan of 50 hours of labor and one machine, as the table shows. Now, suppose that a union negotiates a wage of $20 an hour, including benefits. In this case, it makes no difference to the firm whether it uses more hours of labor and fewer machines or less labor and more machines, though it might prefer to use more machines and to hire fewer union workers. After all, machines never threaten to strike—but they do not buy the final product or service, either. In the final column of the table, the wage has risen to $24 an hour. In this case, the firm clearly has an incentive for using the plan that involves paying for fewer hours of labor and using three machines. If management responds to union demands for higher wages by investing more in machinery, then union workers can be more productive because they are working with more or better physical capital equipment than the typical nonunion worker. However, the firm will need to hire fewer workers.

| Hours of Labor |

Number of Machines |

Cost of Labor + Cost of Machine at $16/hour |

Cost of Labor + Cost of Machine at $20/hour |

Cost of Labor + Cost of Machine at $24/hr |

| 30 |

3 |

$480 + $600 = $1,080 |

$600 + $600 = $1,200 |

$720 + $600 = $1,320 |

| 40 |

2 |

$640 + $400 = $1,040 |

$800 + $400 = $1,200 |

$960 + $400 = $1,360 |

| 50 |

1 |

$800 + $200 = $1,000 |

$1,000 + $200 = $1,200 |

$1,200 + $200 = $1,400 |

Table 15.3 Three Production Choices to Manufacture a Home Exercise Cycle

In some cases, unions have discouraged the use of labor-saving physical capital equipment—out of the reasonable fear that new machinery will reduce the number of union jobs. For example, in 2002, the union representing longshoremen who unload ships and the firms that operate shipping companies and port facilities staged a work stoppage that shut down the ports on the western coast of the United States. Two key issues in the dispute were the desire of the shipping companies and port operators to use handheld scanners for record-keeping and computer-operated cabs for loading and unloading ships—changes which the union opposed, along with overtime pay. President Obama threatened to use the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947—commonly known as the Taft-Hartley Act—where a court can impose an 80-day cooling-off period in order to allow time for negotiations to proceed without the threat of a work stoppage. Federal mediators were called in, and the two sides agreed to a deal in February 2015. The ultimate agreement allowed the new technologies, but also kept wages, health, and pension benefits high for workers. In the past, presidential use of the Taft-Hartley Act sometimes has made labor negotiations more bitter and argumentative; in this case, it seemed to have smoothed the road to an agreement.

In other instances, unions have proved quite willing to adopt new technologies. In one prominent example, during the 1950s and 1960s, the United Mineworkers union demanded that mining companies install labor-saving machinery in the mines. The mineworkers’ union realized that over time, the new machines would reduce the number of jobs in the mines, but the union leaders also knew that the mine owners would have to pay higher wages if the workers became more productive, and mechanization was a necessary step toward greater productivity.

In fact, in some cases union workers may be more willing to accept new technology than nonunion workers, because the union workers believe that the union will negotiate to protect their jobs and wages, whereas nonunion workers may be more concerned that the new technology will replace their jobs. In addition, union workers, who typically have higher job market experience and training, are likely to suffer less and benefit more than nonunion workers from the introduction of new technology. Overall, it is hard to make a definitive case that union workers as a group are always either more or less welcoming to new technology than are nonunion workers.